Fundamental Uncertainty

The 'systems view'

Our current ‘global system of value’ doesn’t really recognize the value of wondering, along with other essential practices, which means a lot of it must take place on the side, and practices such as these need to take their own form.

So I am hoping to more regularly bring some ‘shape’ to some of this wondering, and I am particularly inspired by Rewilding Philosophy by Jess Bohme, who’s writing is one of the few on sub stack I can genuinely engage with; so here I’m experimenting with a ‘weekly publication’ which deals with some of the same things and feelings she explores, which is, more or less in my interpretation, about exploring the ‘right relationship’ on a personal and socio-cultural level to our current reality.

The Mechanistic Interpretation of Systems

When I first read ‘Systems View of the World’ by Ervin Laszlo, and later began to explore the literature and concepts around systems thinking, I was under the assumption that the ‘systems perspective’ was the light at the end of the tunnel.1 Curiously, I had never been taught such a ‘worldview’ or subject at university (today it remains the case that the most insightful things I have ever read I have encountered outside of university) and after reading it, I saw this ‘worldview’ as the answer to most, if not all, of the questions I had.

If we just look at and understand the world as a system, then we can understand it.

I mean, how obvious! The world is one big system, a system of systems of systems, we just need to see how the parts are interacting with one another. The problem is, we have always looked at things as isolated objects, and not at the relationships they have with other things in the world. A systems view is what we need, especially in terms of tackling sustainability!

But it is important to look closer at what this ‘systems view’ means, and I hope to suggest that a ‘systems view’ is often interpreted under an epistemological/cultural paradigm which struggles to comprehend its meaning.

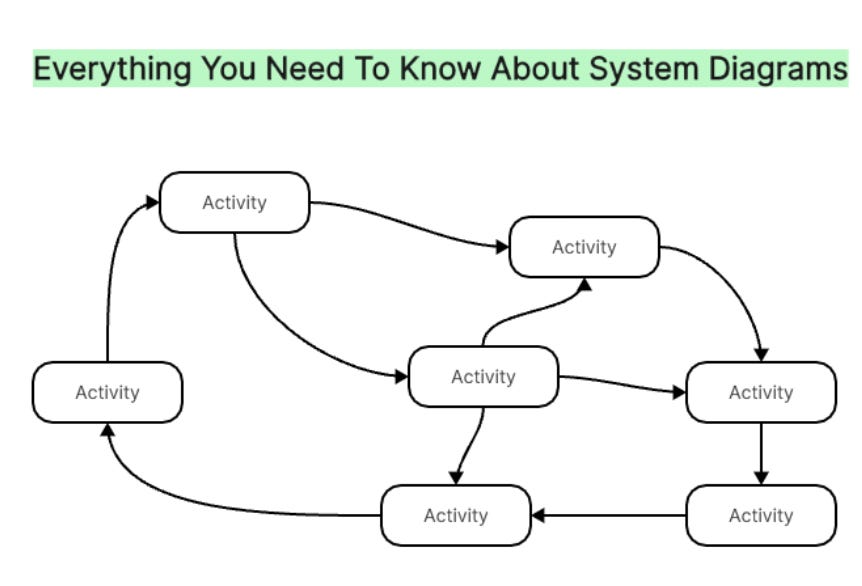

For starters, let’s look at the following diagram, which I just pulled from google images of ‘systems diagram’ and is aptly called ‘everything you need to know about systems diagrams’.

Here, we do not look at activities ‘separately’, but in relation to others. Look at all the connections: one feeds back into the other, and by looking at the connections, we come to a more complete understanding. The one in the middle seems especially important, connecting to lots of different parts- must be a very important activity.

Or this one:

Government is not just government; government works with business, and non-profits, and community organizations. If we see these relationships, we can see the bigger system, and we can understand it all. Herein lies the secret of systems thinking and application. And of course, at the center you have the ‘systems entrepreneur!’, the driving force in systems thinking; the driving force of the paradigm shift.

If we see how the parts work together, we have unlocked the new paradigm.

But this mechanistic, or perhaps post-modern, systems view, does not in any meaningful way change anything. A machine has parts, and these parts are clearly delineated so as to perform specific functions, just like both diagrams above.

This ‘systems view’ just re-invents the notion of ‘object’ as an object which is related to other objects, or ‘parts’ in systems language. A ‘system’ here is composed of objects which has relationships to other objects, forming one big system, and so on and so forth. Government must work with business, which must work with academia, and also non-profits, but also academia and business work together: the complex web!

In this view, there are clear boundaries of objects, or parts, which form one ‘system’, or ‘parts’ in one system. These parts form a higher order system (the same way parts of a blender enable a blender to blend), which means we can still (sort of) wonder about the mystery of emergence.

Importantly, ‘systems thinking’ under this view not only retains the mechanistic view of the world, but also socio-cultural imaginary which informs and supports this world view, like, for example, the entrepreneur at the center, the desire to completely understand the world, and perhaps most importantly the desire to be more ‘productive’ and ‘efficient'; everyone now knows that a systems perspective leads to better results.

To be sure, some ‘systems’ are more ‘mechanistic’ than others (like a blender), but these are mostly the machines the we ourselves have designed and created as tools. The real problem lies in taking a mechanistic view and applying to a complex adaptive system, which occurs quite often, as in the diagram above. Indeed any time human beings, nature, or social organizations are being discussed the mechanistic trap is a possibility.

Fundamental Uncertainty

A lot more can be said about the mechanistic systems view, but I just want to point out that a ‘systems perspective’ (if such a framing is indeed appropriate) requires a much deeper transformation in what it means to be, to know, and to value. It is not about parts working together; it is about sensitivity, embeddedness, adaptivity, entanglement, the open ended unfolding of structure, agency, and emergence.

And at the heart of it all, it is about ‘Fundamental Uncertainty’, the idea that we can never have one complete map of the world, that Truth is always contextual, evolving, and relational; that there are different ways of knowing; that we can make many different maps which point to different parts of reality; and that different maps are useful for different things, but do not need to be integrated into ‘one big map’; there are many maps, many perspectives, many ways of understanding, none of which are truly ‘correct’, but which speak to different things.

Even if, for example, there is a ‘Grand Unifying Theory’ in Physics, this doesn’t really have anything to say about how to deal with the ‘meta crisis’, how to live in community with one another, how to navigate human relationships, how to read literature or write poetry, or what it means to love, explore and navigate questions of purpose, alienation confusion, and much more.

The goal is not understanding; the goal is depth of being.

And so, the real challenge is in trying to embody nuance and produce knowledge in a reality that is an open ended unfolding of structure, agency, and emergence. Boundaries are never truly clear in complex adaptive systems, even though sometimes they are important to draw. The new way of exploring science is not ‘the next step’ towards a complete understanding or map of the world; the ‘new science’ instead involves accepting a fundamental uncertainty, or mystery, at the heart of knowledge production and being in the world, one which sees context, relationality and becoming as the source of Truth.

The following critique is more so from my interpretation, not from Laszlo’s writing